Ranching For The Family

After nearly 100 years of farming and ranching, one Texas family challenged the status quo to build a system that makes ranching fun and easy through regenerative principles.

People say never to go into business with family, but that doesn’t always hold true in agriculture. There is something uniquely rewarding about owning and operating an agricultural pursuit with your family. A bond that runs deeper. Deeper than good years with padding in the bank. Deeper than hard years when tough choices are a daily chore.

Family means more. It’s like soil. When you smell freshly dug soil. When you feel the cool, damp earth run through your hand. When you see layers of rebuilt topsoil and inches of root growth that haven’t been present in years. There’s an overwhelming sense of accomplishment that tugs at the corners of your eyes. A deep sense of knowing. Knowing something will live on, well beyond our time.

Make a positive impact on your land, your livestock and your livelihood.

Take action now towards a more sustainable and more profitable future.

That’s the sense of pride Vance Mitchell has for his family’s 8th-generation ranch ranch at Lolita, Texas. With eyes alight and a jovial smile, Vance fondly tells the story of Mitchell Cattle Company, a regenerative ranch with roots near the Texas coast that he owns and operates alongside his brother, Steve, and their mother, Janet. His husky accent, thicker and clearer than a typical Southern twang, draws you in as he paints a picture of cattle drives and chuck wagons.

Vance’s ancestors started the family business in 1876. The old way of ranching continued until the 1930s, when the family began leasing to tenant farmers. Only 10 miles from the nearest inland bay, the hot, steamy environment was perfect for farming rice. Thirty years later, brackish water crept into the farm’s environment and made the water unsuitable to continue rice, so the operation switched to row-crop farming. With the passing of a longtime tenant, the family began farming on its own. They fell into the same routine as many farm families, filled with spraying, planting, spraying, harvesting and spraying some more. Years went by, and the family tired of the destructive routine.

“We got tired of killing things just to grow things,” Vance remembers. They decided there must be something better.

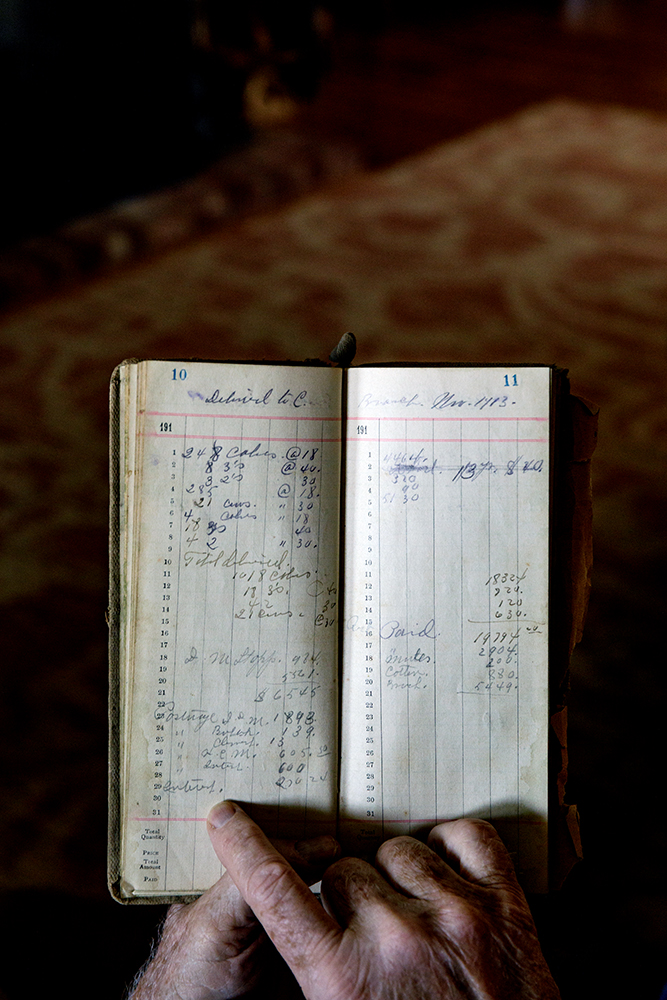

[Left] Eighth-generation Texas rancher Vance Mitchell opens a tally book to show counts, prices and notes from a 1913 entry. [Right] A portrait of Mitchell’s great-great grandfather hangs by the front door of the Mitchell home.

In the 1990s, a desire to change combined with a flexible USDA crop program made the choice straightforward. By then, many of the extended family members had sold their pieces of the original land, so the once-7,000-acre farm and ranch was now down to two locations of around 1,500 acres each. The family practiced set-stock grazing at their homeplace, which made it relatively simple to shut down row-crop farming at the southern location and transition the entire ranch to cattle.

What began as an experiment to fence out a patch of ryegrass grew over time into a full-blown rotational grazing system. The first system in 1992 converted 900 acres of dryland row-crop to grazing with nothing but fence, water, rest and cattle ready to graze. The family decided against planting further, choosing to let nature repopulate the soil without intervention. That year, the Mitchells ran 200 cows through 10 large paddocks. Although many of their fellow ranchers were skeptical they’d succeed, the family never looked back.

Led by the ranch’s original innovators, Vance’s parents, Mike and Janet, the grazing program grew incrementally over a long period of time, and the family learned through a lot of trial and error. Early challenges were primarily based on infrastructure, with water and fencing high on the list. Back then, the Mitchells used a water trailer and high-density polyethylene pipe to move the water with the cattle. With large paddocks and moves only every 5-to-7 days, moving the water was manageable.

After more learning and growing, the Mitchells decided to double the number of paddocks and try 8-foot-by-16-foot concrete troughs to supply eight paddocks at a time. In an area where ranching sometimes means checking heifers during a hurricane, the central alleyways that led to the concrete troughs quickly became mud pits. Eventually, Vance and Steve divided the paddocks further and built a system using 12 permanent troughs to water four paddocks at a time. They also converted the temporary paddocks into more permanent ones, which allowed them to focus on the cattle and keeping on top of the grass.

“The ranch evolved over 30 years. We started with 10 paddocks of 100 acres each. Now we can graze 96 paddocks if we want to. We didn’t make that change overnight,” says Vance.

While the transition was manageable, it wasn’t without challenges. Vance was in his mid-30s and running a feedstore full-time after a career where he dabbled in oil and gas, then banking and real estate. Steve, six years younger than Vance, served in the Marines during the Gulf War before starting a career as a firefighter in Austin. Their strong commitment to family kept them involved over the years and eventually brought them both back to the ranch full-time.

“We try to keep it family,” Vance says. “Our goal here is not only to make a profit but to keep the ranch as long as we can for the continuing generations.”

Regenerative management has certainly been a family wide commitment for the Mitchells. Vance attributes much of the ranch’s success to early learning from Stan Parsons. Vance’s parents were among Stan’s first pupils, attending Ranching for Profit in 1985. Vance and Steve have both attended the school three times over the course of their ranching careers.

“The most important thing we learned about was rest. You have to create a system to limit grazing exposure. Start by creating enough paddocks to give the pasture adequate rest. The next priority is water availability. You need to create a system that has enough water points to support your paddocks. Finally, you need to decrease your overhead,” Vance explains.

“Controlling overhead is crucial to maintaining profit, and regenerative grazing has to be profitable, or no one is going to do it.”

Even after 40 years of using rotational grazing practices, Vance still takes advantage of opportunities to learn more. Vance had known about Noble Research Institute for many years, so he jumped on the opportunity to attend an educational course on the fundamentals of regenerative ranching in Ardmore, Oklahoma, last year. The class was a nice refresher, and Vance enjoyed the opportunity to engage with like-minded folks.

“[The Noble course] really reinforced what we’ve been doing successfully on the ranch. It also reminded me of a few things we need to start doing again, like soil and forage tests,” says Vance.

Today, Vance and Steve successfully run a 500-Beefmaster-cow herd. Though their primary revenue is the cow/calf operation, the team also retains stocker calves, depending on moisture and the market. In a good year, they will also run a heifer-development program on the side.

The brothers, along with one ranch hand, Jesse, move cows continuously. The two locations are split into 48 and 30 permanent paddocks, doubling and tripling that with temporary fencing if necessary. Movement depends on moisture, and by extension, how the pasture responds, so it varies from every half-day to every three days. The goal is to “eliminate the second bite,” Vance recalls, citing one of Parson’s core principles. (‘Eliminate the second bite’ is a widely adopted regenerative principle that says cattle should only take one bite from each clump of grass in the paddock, which leaves enough plant matter to stimulate root growth and maintain ground cover.)

Practicing regenerative grazing has provided benefits beyond simply increasing stocking rates. The cattle became calmer. The soil became richer. The grass became more manageable, and the pests were nearly eliminated. In an area where an oncoming mosquito sounds like a crop duster, Vance laughs, because when his vet calls, it’s to tell him he won’t be buying wormer for another year.

“People don’t believe we don’t have parasite problems. But if you don’t come back to a pasture for 45 days, and you let the grass get tall enough, it’s just the way it works,” he says. “We take fecal samples regularly and have since we started. It’s not that we don’t have parasites, we just let nature take its course, and we rarely have to intervene.”

The only time we’ve fed hay in the last 30 years was once during the 2011 drought, and we won’t make that mistake again.

Vance Mitchell

To Vance, regenerative grazing means matching nature with what you do. To achieve a more holistic approach, Vance often steps outside the norm of practices in his region.

“The extension service has had four or five show-and-tells out here. People show up real curious.” Vance pauses with an exasperated laugh. “But none of them believe what we do. They just can’t fathom doing this the way we do it. Moving cows every day doesn’t make sense to them. What we do is not very accepted.”

One major difference is that the Mitchells calve in July while most of their neighbors calve in January. This has reduced labor and inputs, as the cows are fat and ready when going into calving.

“The only time we’ve fed hay in the last 30 years was once during the 2011 drought, and we won’t make that mistake again,” Vance says. “The cows just don’t need anything else when getting ready to calve.” The regional deer rut is in September/October, and they turn bulls out on October 1st. “If that’s when nature is going to do its breeding, then why don’t we?”

It’s easy to wonder whether Vance’s ancestors foresaw a future where he, Steve and Janet would be working to restore their land to the natural state it was in when the family settled years ago. By mimicking nature rather than fighting it, Vance and Steve get to relax and enjoy watching the cattle. Janet is still involved with recordkeeping.

“My mother, Janet, is now 89 years old. She still does the books and keeps her thumb on my brother and I. Steve is 60 and I’m 66,” Vance says.

“We would never go back to set stocking, because it doesn’t make any sense at all. We could lease our land for farming, and the money would be about the same. But we enjoy this much more. As my brother and I say, our backsides don’t fit tractors anymore,” he chuckles, with one of those jolly laughs that makes you grin. “Everyone thinks rotating cattle is hard, but it’s easy, and it doesn’t take much time.”

By focusing on infrastructure to support their management practices, Vance and Steve have built a system that makes regenerative grazing easy, resulting in calm cattle, low-input routines and an economical ranch that is fun for the family to manage.

Make a positive impact on your land, your livestock and your livelihood.

Take action now towards a more sustainable and more profitable future.

Comment