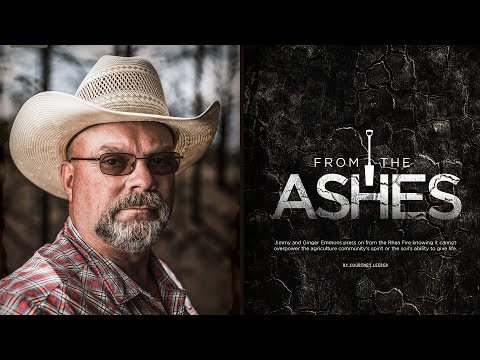

From the Ashes

Jimmy and Ginger Emmons press on from the Rhea Fire knowing it cannot overpower the agriculture community’s spirit or the soil’s ability to give life.

Jimmy Emmons rarely goes to the field without a shovel.

Once, when he and his wife, Ginger Emmons, had traveled to Indiana for a farm conference, he realized he had left his shovel at home. Ginger laughs, remembering they found a farm supply store and bought a new one. Now the replacement is his favorite.

Jimmy often uses this shovel to unearth samples of the rusty red soil of Dewey County, Oklahoma, where he and Ginger farm and raise cattle. Both have always depended on this land. Before the high school sweethearts married 36 years ago, they grew up on farms just 6 miles apart near their hometown of Leedey.

This soil has helped them build their lives, and now they help build up the soil.

After scooping a spadeful of the loamy substance, Jimmy looks for qualities that point to a healthy foundation for the farm. Through the last three decades, he and Ginger have sought ways to nurture the soil and its ability to support life: plant, animal and their own.

The journey has led them to try ideas against the norm.

Jimmy remembers the earthy smell of freshly plowed soil. Tillage was long believed to be the best way to prepare fields for planting. But in the 1990s, he realized the practice was costing him carbon, an essential component of healthy soil, and ultimately soil itself. So, he turned to no-till.

Most recently, he has added diversity to the earth’s palate by planting cover crops — sometimes as many as 30 species in one field. Growing plants when the ground would otherwise lie bare shields the soil from being swept away by rain and wind. The mix of root systems feed the soil in ways a single species cannot. The cover crop can also, in some cases, provide a source of forage for cattle when wheat, the traditional forage crop in the area, is out of season.

The soil has responded. More earthworms wriggle through the sediment, which points to a more vibrant community of microorganisms below. And the soil now needs less supplemental nutrition. Jimmy has been able to cut back on fertilizer by 40 percent.

Healthier soils also hold more water, a desirable quality especially for farmers, like Jimmy and Ginger, in areas prone to drought. On April 12, 2018, the Emmons farm had seen less than an inch of rain in the past 140 days.

Not even soil health champions are immune to drought and its fallout.

A Day to Remember

Jimmy’s interest in the soil has not gone unnoticed. In mid-October 2017, he learned he would receive the state’s first Leopold Conservation Award, which is part of a national program that honors farmers and ranchers for their commitment to the land.

The morning of April 12, Jimmy and Ginger rose early to finish chores around the farm before heading out on the two-hour drive to the award ceremony at the Capitol building in Oklahoma City. Afterward, they planned to stop by their 5-year-old grandson’s T-ball game.

Jimmy’s cellphone buzzed in his pocket a couple of times during lunch, but it wasn’t until he and Ginger pulled in at the softball field that they realized something was terribly wrong.

Another call came in, this one from Ginger’s friend LaDena Kauk. LaDena and her husband, Mike Kauk, own a local construction business. The couples had gone to school together and remained close. Jimmy picked up the phone.

“I don’t want to alarm you,” LaDena said, “but you might want to come home. There’s a fire.”

LaDena’s voice was calm, but Jimmy could tell the façade was for his and Ginger’s benefit only.

“How bad is it?” Jimmy asked as he and Ginger jumped back into the pickup.

“If you turn on the news, you’ll understand,” she replied.

Ginger turned the radio to the Woodward station, and they listened in rising alarm as the reporter announced fire department after fire department called in to control the flames.

LaDena sent the first photographs of the fire when the Emmonses were within 50 miles of home. It was headed straight for their house.

As Jimmy and Ginger approached home, they saw 60- to 70-foot walls of fire light the night’s sky. For weeks, they had been watching the wheat bake in the sun. Now they watched it burn.

Firefighters and Mike Kauk with his company’s bulldozers had built firebreaks around the home to protect it from flames of what had become known as the Rhea Fire.

Later, the Oklahoma Forestry Services would tell Jimmy the fire was burning 118 acres per minute as it went past his house that night. At the last minute, the winds had shifted. The home was spared.

Rhea Fire Facts

Fire started: Approximately 2 p.m., Thursday, April 12, 2018

Cause: Unknown

Date of containment: Thursday, April 26, 2018

Size:

286,196 acres

Location: Primarily Dewey County, Oklahoma

Number of responding fire departments:

At least 179

(Rhea and 34 Complex fires combined; 34 Complex Fire also started April 12 in Woodward County, north of Dewey)

32 states

provided resources to assist wildfire firefighting efforts across Oklahoma from Jan. 22 through April 26, 2018

Source: Oklahoma Forestry Services

Save the cows

Jimmy and Ginger thought they had dodged the bullet. Then, the next day, two turkey hunters were on land just south of the Emmonses’ when they heard what sounded like a gunshot.

Strong winds had created a dance among the power lines. Leaping cables crossed, and the ensuing sparks hit the dry grass. Another fire was born. It consumed a neighbor’s barn filled with hay before heading toward the Emmons home again. Mike’s bulldozers and the Leedey fire department returned to try to extinguish the flames.

“The panic had set in at this point,” Jimmy says. “You’re thinking: ‘What do you try to save? Is it photos or documents, the dogs, the cattle in the lot?’ All that is going through your mind as you’re trying to figure it out on the fly.”

Up to 50-mile-per-hour winds shifted in every direction, at one point pushing the fire away from the house but putting more cattle in danger. Jimmy and Ginger together with Karson Leibold, who has worked as the Emmonses’ ranch hand for 10 years, sprang to action to save the cows.

At one point, Leibold was nearly run over by the fire while moving a group of cows to safety. Most darted through the open gate to shelter, but one cow would not budge. Ginger remembers Leibold’s frantic call and telling him he needed to save himself.

“I kept telling Ginger and Karson, ‘We want to save the cows, but let’s not do anything to lose ourselves,’” Jimmy says. “The fire was moving so fast, and we’d never had so much wind. We just didn’t have time to reach all the cows. It was a helpless feeling.”

That first night, Jimmy and Mike were in bulldozers until 10 p.m. trying to build firebreaks and shield what land they could. They could feel the heat from flames 50 feet away, which the firefighters continued to battle.

Eventually, Jimmy and Ginger left the burn area. The smoke was too thick, and there was nothing more they could do without hindering the fire department.

The house was quiet that night as the couple made their game plan for the next day. They knew they had not been able to reach all of the cattle in the fire’s path. They didn’t know how many cows would be left standing in the morning.

Miracle in the clearing

The sun was just peeking over the horizon when Jimmy rushed to one burnt pasture and Ginger to another.

Ginger went to a lot that had been filled with eastern redcedars, an invasive species that contributed to the intensity of the fire. Her stomach was in her throat, she recalls, as she forced herself to walk across the blackened ground and through the thicket of charred trees.

“I just knew I was going to find all of the cows dead,” she says. “There was no way that they could have survived with so many cedar trees there to fuel the fire.”

But in the back corner of the pasture, on top of a hill, the cattle were grazing a patch of grass that somehow had not burned. It was an area less than an acre in size and the only sign of life within seeing distance.

“I could not believe they were alive,” she says. “Not even one hair on them had been singed. I was so grateful they weren’t hurt.”

Jimmy, too, found live cattle. But the uncontrollable winds made it difficult to stay ahead of the fire.

“To remedy the cow situation, we just didn’t always know what to do next,” Jimmy says. “I’d rush to one place. Ginger would rush to another. We moved cows from one pasture to another, sometimes even loading them up in trailers to haul out. But the fire was so hot that even green pasture burned.”

Ask the Expert: Tim Boatright

Tim Boatright, an agricultural equipment mechanic at the Noble Research Institute, serves as the captain of the Shady Dale Volunteer Fire Department in Love County, Oklahoma. He has volunteered as a firefighter for more than 15 years.

Q: What is it like to serve as a volunteer firefighter?

A: Volunteer firefighters do not work set hours at the department. Most of us have full-time jobs. I’ve worked as an agricultural equipment mechanic for the Noble Research Institute for three years. Previously, I served as a technician with John Deere for 30 years.

As a volunteer, you’re always on call. We respond to about 90 percent of the emergency calls sent out since there are so many more volunteer fire departments than paid, especially in rural areas. Of the 1,000 fire departments in Oklahoma, 968 are volunteer.

Our crew numbers vary based on volunteers and their work schedules, so we never know how much help is coming until we’re on the scene.

Because of this, it’s important that we have relationships with other fire departments. In 2006, the state implemented an automatic aid response, which is a multistation page based on department zones. When an emergency call is received, at least three fire stations are expected to respond. The first fire officer on the scene determines if and how much more help is needed.

We receive some funding from the state, but it’s not enough to cover all our expenses. We depend on fundraising drives for water and food supplies. Each volunteer department has a rehab group (made up of volunteers) that makes sure firefighters have enough supplies to get them through each call. The bigger the call, the bigger the crew and the more supplies needed during and after the call. Monetary donations made to a station can go directly to a station for use where needed or to a rehab group to stock supplies.

Landing on Mars

In the midst of the chaos, Jimmy called Jim Johnson, a Noble Research Institute soils and crops consultant. Johnson and Bill Buckner, Noble president, visited the Emmonses on Saturday, April 14.

“I was not prepared for the vastness of the devastation,” Johnson says. “It looked like we had landed on Mars. The smoke was still thick. We had to wear safety goggles and dust masks just to get around.”

Power lines were down, creating a maze to navigate. Yet linemen were already out, just feet from the flames, working to restore electricity. Jimmy and Ginger had been without power since Thursday. Johnson and Buckner brought a generator for the house, but the linemen were able to restore the power by that evening.

The winds were still blowing, and Johnson remembers watching dirt flow through a ditch like a river. The fire had burned around some areas that should have been candy to the flames. Others burned so hot that not even ash was left.

“It didn’t make sense as to why some areas burned and others didn’t,” Johnson says. “The only thing I can say is God must have put his hand on the land and said, ‘This guy has suffered enough.’”

Jimmy and Ginger’s immediate concern was what to feed the cattle. They had lost a stack of hay, and 120 of their 250 cows had lost their pastures. In the meantime, some of those cows were giving birth.

Johnson helped Jimmy calculate how many days of forage he had left and plan where he could move the cattle next. Some would be placed on triticale pasture originally intended for hay until drought stunted its growth. Jimmy had been disappointed with the pasture, but now he is thankful for it.

Johnson and Buckner also helped patch fences along some of the 23 miles of fence line the Emmonses will need to repair. About 18 miles will need to be completely replaced. A few weeks later, they learned a government program would reimburse 75 percent of the costs. But they would still need to be able to cash flow the expense up front.

“Ginger wanted to figure how much money we’d need to put back for the fence repairs,” Jimmy says. “I told her, ‘You don’t want to know that number.’”

He laughs but adds: “It’s overwhelming. That’s the word I’ve been using a lot lately: ‘overwhelmed.’”

A long road ahead

By the time the Rhea Fire was fully contained April 26, it had consumed 286,196 acres, or about half the county. Volunteer firefighters from across the country had come to fight the fire.

“Most of them didn’t know the lay of the land,” Jimmy says. “But they fought relentlessly, and they took care of each other. They are true heroes.”

The fire crossed about half the land the Emmonses manage, but they are quick to say they were fortunate. Their home stood, and most of their herd was intact. Of their 250 cows, they lost only two — not to fire but to smoke.

They also lost an outbuilding with a few pieces of machinery and some hay. Some of their neighbors lost their homes. Every acre of grass. Half their herds. All of their equipment. Two people lost their lives.

“It makes us feel pretty blessed compared to what others went through,” Jimmy says. “We’re very thankful.”

Donations of hay and fencing supplies poured in from around the country. Jimmy, who serves on the local conservation district board, was among community leaders who helped ensure people, especially those who had lost hay-moving equipment, received what they needed.

Students from the local FFA chapter came out to help Jimmy and Leibold fix fence two weeks in a row. The community also banded together to buy the Leedey fire department a new truck.

“It’s going to be a long, difficult road to recovery for many people around here,” Jimmy says. “But farmers are some of the most resilient people in the country. Most of us try to stay positive or we wouldn’t be able to stay in agriculture. You’ve got to have that fortitude.”

Promise of Better Days

Within days of the fire, green began to sprout from the scorched surface of the soil.

Five weeks later, remnants from the fire — melted stop signs, downed fences, the scent of charred cedar — still filled the countryside. But, Jimmy says, life moves on. There are cattle to tend and decisions to make. Many, including him, will sell cattle that the land cannot currently support.

Much of the land will be better off in the long-run because of the Rhea Fire, Jimmy says.

This land evolved under fire, which makes fire a natural — and essential — part of the landscape. Once it’s removed, brush becomes more difficult to control. Unruly vegetation leads to a heavier fuel load that, once an unplanned fire has been sparked, leads to hotter and more dangerous wildfires. The No. 1 contributor is eastern redcedar.

“That’s one of the silver linings,” Jimmy says. “Cedars are a big problem around here. This land wasn’t meant to have them, and the fire did a good job of clearing them out.”

The challenge is going to be getting everything back in working order, Johnson says. Burned pastures will need to rest for at least a year. Noble consultants stay connected with Jimmy and others in the area. They plan to make a trip to Dewey County to help with recovery once producers are ready to start making grazing management plans.

“Jimmy has some advantages for recovery,” Johnson says. “Fire is a pretty big equalizer, but he is going to see his grass rebound better and faster because of his and Ginger’s good grass management practices.”

Jimmy and Ginger have been careful not to overgraze their pastures, and they’ve controlled eastern redcedar on what land they could. Their biggest advantage, though, Johnson says, will be their use of cover crops.

Within weeks of the fire, Jimmy had sown a mix of species — sesame, corn, soybean, milo, even watermelon and okra — as cover crops for wheat pasture. A practice he originally adopted for soil health will now pay off in the form of forage he would not have if he farmed in the traditional wheat-only system.

“The resiliency of our soils is greater than the resiliency of the agriculture community, and that’s saying a lot,” Jimmy says. “We don’t give up, and neither does the soil.”

Comment