The Feral Hog in Oklahoma

Introduction

Oklahomans have enjoyed or cursed feral hogs (Sus scrofa) in the southeastern and eastern parts of the state for several years. Oklahomans in many other areas of the state are following suit. At one time, domesticated hogs were managed as free ranging livestock in parts of the state. These domesticated hogs would often become feral and were hunted or trapped for meat. Managing domesticated hogs as free ranging livestock is not a common practice any more. However, feral hog populations remained and are spreading throughout the state. As feral hog populations have expanded, debate about the pros and cons of their presence has become more intense. Many landowners, especially farmers, cringe at the thought of feral hogs becoming established on their property. Some hunters, on the other hand, look forward to having them on their favorite hunting grounds. To some hunters, the feral hog represents a formidable trophy worthy of paying money to hunt. To some landowners, the potential of leasing feral hog hunting rights makes it a bit easier to accept the presence of the animals. Regardless of landowners’ and hunters’ opinions, feral hogs have proven their ability to survive and procreate, and will probably be around for a while.

All photos by R.L. Stevens except where noted.

This publication is a creative work fully protected by all applicable copyright laws, as well as by misappropriation, trade secret, unfair competition, and other applicable laws. Except for appropriate use in critical reviews or works of scholarship, the reproduction or use of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, digital imaging, and in any information storage and retrieval system is forbidden without express permission of the authors.

Feral hogs are wild swine from domestic ancestry and belong to the family Suidae. There are three types of wild hogs found in the United States: feral hogs, Eurasian wild boar (Russian) and hybrids between these two types. All of these types are the same species.

California, Florida and Texas have the highest numbers of feral hogs in the U.S. Some of the Hawaiian Islands have substantial populations, and Oklahoma’s population is healthy and growing. Despite their widespread populations, feral hogs are not indigenous (native) to the U.S.

Although the collared peccary or javelina (Tayassu tajacu) is vaguely similar in appearance to the feral hog, it is a different animal. The javelina is native to the southwest U.S. and belongs to the family Tayassuidae. The identities of these animals are sometimes confused, but the feral hog belongs to a different species, genus and family than the javelina.

Ancestors of swine (Suidae family) date to the Miocene. During the period when the world was shifting and forming new continents, the swine family was excluded from the North American continent. It probably was not until the discovery of the continent by Europeans that swine found their way into what is now the United States. Early explorers such as Hernando Cortes and Hernando de Soto brought over domesticated swine, but it was not until the 1930s that the Russian wild boar was introduced.

Today, there are areas in the U.S. where the pure Russian wild boar (native to Europe and Asia) can still be found due to importation for sport hunting purposes. However, most feral hogs are from domesticated swine. Feral hogs are wild, but are not a different species than domestic hogs or Russian boars. Webster’s dictionary defines feral as having escaped from domestication and become wild. Hence, all feral hogs in the U.S. up until the 1930s were from domestic stock. In a few areas where the Russian boar was imported for sport hunting, escapes have occurred resulting in feral/Russian crossbreeding.

The feral hog has been very successful in expanding its range and increasing in numbers. Its success can be attributed to several factors: free ranging husbandry methods, introduction and re-introduction of feral hogs by hunters, water development in arid areas, improved range condition through better livestock grazing practices, the animal’s ability to adapt to a variety of situations and eat a variety of foods, and the hogs’ ability to reproduce rapidly. Feral hog populations also have benefited from increased disease control in the domestic livestock industry.

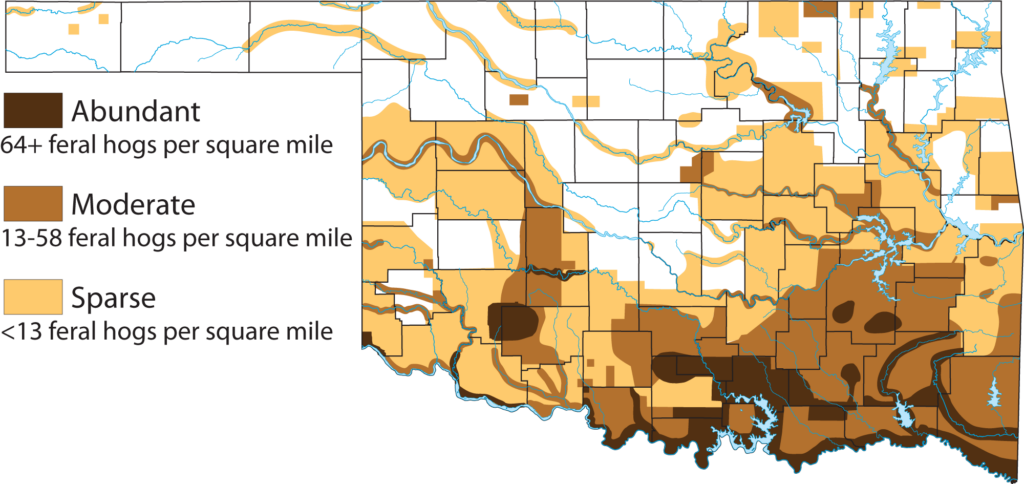

Historically, there are no accurate accounts of feral hog numbers or their distribution in Oklahoma. Like the white-tailed deer, their secretive nature makes it difficult to obtain an accurate count. Statewide distribution is easier to estimate, but is mostly limited to knowledge of their presence or absence in a particular county. During the summer of 2007, Noble Research Institute wildlife and fisheries staff initiated a statewide survey to obtain a better estimate of the distribution and number of feral hogs in Oklahoma. The survey was conducted by wildlife and fisheries intern David Rempe. Agencies surveyed included the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, Natural Resources Conservation Service, Oklahoma State University Extension and Oklahoma Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services. Representatives of each of these agencies were contacted in every Oklahoma county and asked if feral hogs were present in the county. If they were, we asked them to estimate density based on three categories: abundant (less than 10 acres per hog), moderate (11-50 acres per hog) or sparse (greater than 51 acres per hog). They were also asked the year that feral hogs were first observed in the county.

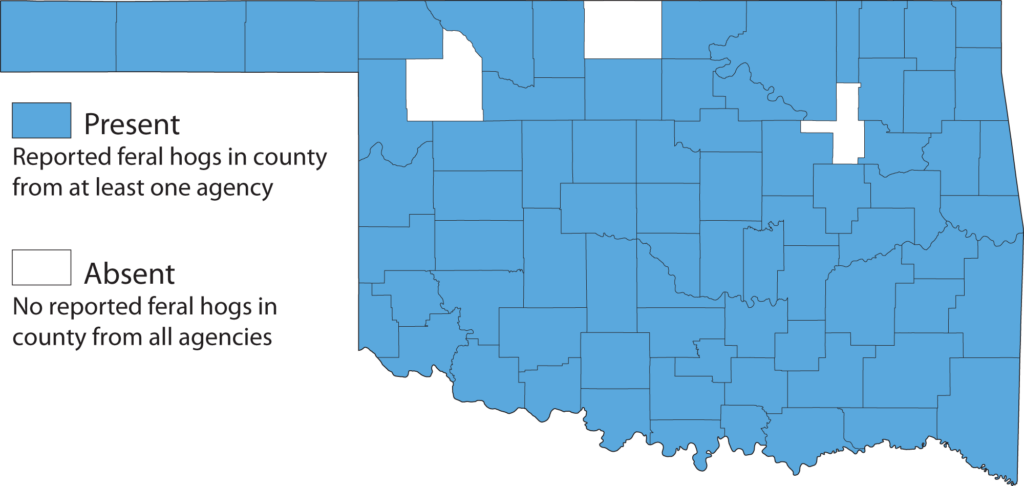

Figure 1

Figure 1. Presence of feral hog in Oklahoma by county (2007). Recent evidence indicates that feral hogs are now present in every Oklahoma county.

Respondents indicated that feral hogs were present in 74 of Oklahoma’s 77 counties (Figure 1).

Figure 2

More recent anecdotal evidence suggests that feral hogs are likely present in the remaining three counties. Based on respondent estimates, the feral hog population in Oklahoma was between 617,000 and 1.4 million. The lowest agency estimate of the number of feral hogs in Oklahoma was 430,000 and the highest was 1.6 million. The average low and high estimate for all agencies was 617,000 and 1.4 million, respectively. Density estimates were assigned to mapping grids representing 20 square miles. These grids did not follow river drainages where respondents indicated most feral hogs were located. With inherent mapping error taken into account, the estimated feral hog population in Oklahoma was calculated to be 500,000 or less (Figure 2).

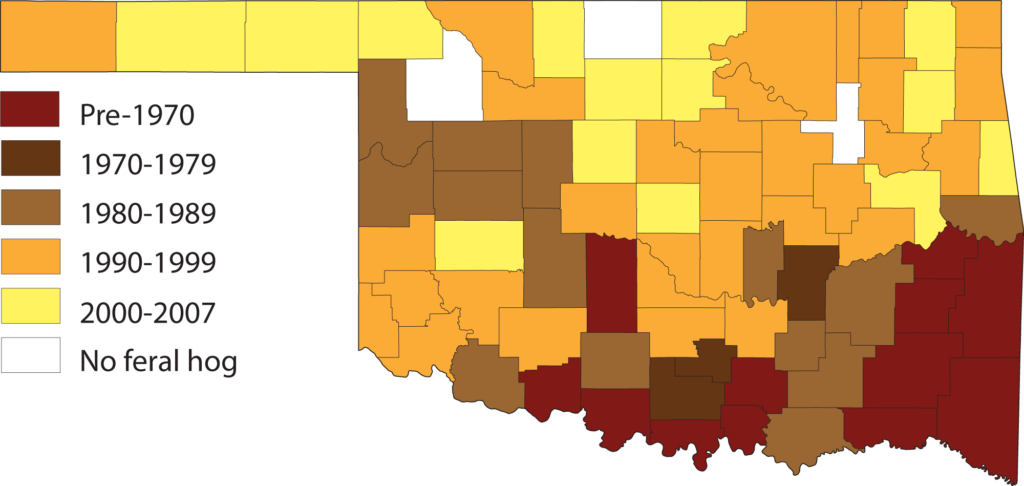

Figure 3

Several variables influenced the estimated year that a feral hog was first present in each county (Figure 3) including the absence of records for first observations, unreported first public sightings and the respondent being new to a county. However, the earliest record of feral hogs in Oklahoma is from the south-central and southeastern portions of the state. It appears that feral hog populations have been spreading across the state from the southeast to the northwest.

Determining distinguishing characteristics between all possible crosses of domestic, feral and Russian hogs can be difficult. Studies have been conducted using DNA, skull measurements, external body measurements, coat coloration patterns, bristles and other criteria, but definite determinants have not yet been developed for all possible crosses. Therefore, it should be noted that the following descriptions are general and relative.

Description

In general, a feral hog looks like its domestic counterpart. Coat coloration patterns can vary from solid black, brown, blond, white or red to spotted (various combinations of black, white, red and brown) or belted. A belted hog has a white band across the shoulder and forelimbs. Feral hog bristle length is generally longer than a domestic hog, but shorter than the hybrid or pure Russian. Feral hogs can reach 3 feet in height and weigh over 300 pounds, however, sows and boars in the 100-150 pound range are more common. A boar has four continually growing tusks that can be extremely sharp and may reach 5 inches before they are broken or worn off from use. Tusks are used for defense and to establish dominance during breeding. Male feral hogs also develop a thick, tough skin composed of cartilage and scar tissue on the shoulder area, which is sometimes referred to as a shield. The shield develops continually with age and through fighting.

The pure Russian boar is generally light brown or black with a cream or tan color on the tips of the bristles. Its underside is lighter in color, and its legs, ears and tail are darker than the rest of the coat. Its bristles are the longest of the three types of wild hogs. Pure Russian boars have longer legs and snouts, and their head to body ratio is much greater than that of feral hogs. They also tend to have shorter, straighter tails. All types of wild hogs can raise the hair on the back of their necks and shoulders producing the “razorback” look.

Feral/Russian crosses exhibit combinations of features from both the feral and the Russian hogs. Bristle length in the hybrid is longer than the feral, but shorter than the Russian. Hybrids exhibit the smallest bristle shaft diameters. Striped patterns on the young are sometimes thought to be an indicator of pure Russian or feral/Russian crosses; however, this pattern has also been found in all three types of feral piglets and therefore is not a reliable method of identification.

Home Range, Reproduction and Activity Periods

Feral hog home ranges can vary from 0.4 to 19 square miles, and they have been known to travel up to 15 miles. Availability of water and food, and sexual activity are probably the three most important factors determining home ranges; thus, fall and winter ranges are likely to be larger than spring and summer ranges. Males generally have larger home ranges than females, especially during breeding season. Boars usually travel and feed by themselves unless they are with a receptive sow. Groups of wild hogs called “sounders” generally consist of sows and their young.

Feral hogs are prolific reproducers, having as many as two litters per year, with each litter consisting of four to 10 young. Good habitat, nutrition and weather allow production of the most young with peak numbers usually born in late winter or early spring. The gestation period is about 115 days, and litters consist of a 1:1 male to female sex ratio.

Feral hogs can be active any time of the day depending on season and food availability. Hot summer temperatures make them nocturnal (active at night) to avoid excessive heat. During cooler months, when unmolested, feral hogs are active primarily in early morning and late evening. Scarcity of food and poor habitat may cause them to extend their active hours regardless of the season. Hunting pressure or other harassment may also cause them to shift activity periods and home ranges for a short period of time.

Physical Characteristics Photos

Food Habits

Feral hogs are omnivorous, meaning they will eat both animal and plant matter. They are also opportunistic feeders, which means they are masters at taking advantage of opportunities or circumstances that may supplement their nutritional needs. These definitions can be shortened by saying they are opportunistic omnivores. With that in mind, it becomes pretty clear what feral hogs will eat … almost anything!

Although feral hogs are omnivores, the season or time of year determines the bulk of their diets’ contents. Spring diets include grasses, forbs, roots and tubers. Summer and fall diets consist primarily of soft and hard mast (fruits) including grapes, plums, prickly pears, mesquite beans, acorns and persimmons. Other important food categories in feral hog diets are mushrooms, carrion and live animal matter such as birds, eggs, snails, insects, earthworms and other invertebrates. The feral hog has an acute sense of smell enabling it to be an efficient predator when given the opportunity. Various agricultural crops are also eaten, with peanuts, corn, milo, oats, wheat and soybeans among their favorites. Nutrition is generally poorest in the winter and summer, and best in the fall and spring.

Competition and Environmental Concerns

Feral hog food preferences can hardly be mentioned without discussing competition with native wildlife. The potential for feral hog competition with native wildlife for food, cover, water or space should always be a concern for landowners and managers. There is documentation of competition for food with deer, turkey, waterfowl, squirrel, raccoon, opossum, foxes, bobcat, collared peccary, bears, sandhill crane and chipmunks. They may also consume significant amounts of native or introduced cool-season forages managed for livestock. A landowner or manager may not be concerned with all of these species, but they are included here to emphasize the diverse diet and impact of the feral hog. Competition for food is usually seasonal. In Oklahoma, for instance, competition for acorns between feral hogs, white-tailed deer and turkey may be most intense during fall and winter.

There have been many studies examining the effects that feral hogs have on vegetative communities as a result of feeding and/or rooting. These effects can alter ecological processes such as water and mineral cycles. Rooting, if severe enough, can also alter successional stages within plant communities. The effects that these activities have on vegetation may be positive or negative depending on climate, plant community and land use goals of the property manager. Positive effects may include a decrease in insect pests, increased quality of seed beds, increased water infiltration, a shift in plant succession toward increased diversity, accelerated decomposition of organic matter and increased mixing of soil horizons. Negative effects may include soil erosion, consumption of native seed crops, consumption of threatened or endangered species, altered plant succession and reduction of overall species diversity.

Habitat Preferences

Feral hogs can adapt to just about any plant community. However, they prefer moist bottomlands or riparian areas (soil and plant communities influenced or created by flooding or shallow groundwater) associated with streams and rivers, or other areas with adequate water. Another feature associated with these types of plant communities is dense vegetation. Feral hogs seem to prefer riparian areas with good distribution of dense vegetation to use as escape cover and concealment.

Feral hogs can also be found in upland areas. Mast, crops or other food sources generally attract them to these areas. Ponds or lakes and dense vegetative cover located in uplands also facilitate use of these areas.

Feral Hog Sign

There are several indicators that betray the presence of feral hogs in a given area. Some of these are easily recognized while others are not. Common signs include tracks, rooting, wallows, rubs and scat.

Tracks are probably the most difficult to identify due to their resemblance to deer, goat and sheep tracks. The key point in distinguishing a hog track from a deer track is the rounded or blunt tip of the toes. The toes of a hog track on a firm surface tend to be more splayed than a deer track from a standing or walking deer. A hog track also appears rounded or square when compared to a deer track of similar width. Deer tracks made by standing or walking deer appear heart shaped and have more pointed or sharply tipped toes. The presence of dew claw marks with feral hog or white-tailed deer tracks is not an indicator of sex as commonly thought. Dew claw marks associated with any hog or deer track simply means the animal was running or stepping on a soft surface. The relative size of the track is the best indicator of sex or age of a hog or deer.

Rooting is a common activity and is done year-round in search of food. Depending on food source and availability, rooting can be more intense seasonally. Rooted areas can be very large, sometimes covering entire fields. In softer soils, rooting can reach a depth of 3 feet. This rooting habit is the prime reason for the feral hog’s bad reputation with landowners. Rooting is easily recognized and can be beneficial or destructive to fields and vegetation (see Competition and Environmental Concerns), and can create the potential for damage to farm equipment and injuries to livestock.

Wallows are depressions in wet areas created by rolling and rooting, which enable hogs to coat their skin with mud. Wallows are created and used to escape heat and insects, and often fill with water, making them more effective for these uses. Wallows are used more frequently during hot summer months. Water sources can become contaminated from hog wallowing activities, and riparian habitat can be negatively altered. Wallowing can cause muddy water, excessive algae blooms, stream or pond bank erosion and reduced aquatic vegetation. All of these impacts can negatively affect water quality and may lead to decreased livestock use and reduced fish production.

Rubs are generally made after wallowing and are most often associated with wallows. The purpose of rubbing is for the hog to scratch and remove dried mud, hair and external parasites. Feral hogs use just about anything to rub on, including trees, fence posts, rocks and utility poles. Feral hogs seem to have a preference for rubbing on creosote-treated posts or utility poles. Rubs are most easily found during the summer and fall months.

Another indicator of feral hog presence is scat, a term for manure or droppings. Like tracks, feral hog scat is usually shorter-lived and is harder to identify or confirm than other signs indicating their presence. Feral hog scat can look similar to dog scat in shape, size and consistency; however, it can be variable.

Signs of Feral Hogs Photos

The feral hog has received a lot of credit for various depredation and disease problems, but is sometimes wrongly accused. Feral hogs, like all animals, are susceptible to many infectious and parasitic diseases, but probably cause more problems through rooting, wallowing and depredation.

Depredation

Feral hog depredation on crops, livestock and wildlife can be extensive. In one instance, monetary loss in peanut crops damaged by feral hogs exceeded $40,000. In another instance, feral hogs rooted along freshly planted corn rows, consuming the seed and causing a significant loss of money and labor. Seedling corn has been similarly affected.

The most extensive crop damage usually occurs at planting time or when a crop is nearly mature. Of all landowners, farmers are probably most adversely affected and have the most negative opinion of feral hogs, especially those whose property adjoins riparian areas or other properties with feral hog populations. Ranchers seem to have mixed opinions of feral hogs, depending on the amount of damage incurred to forage and stock, and whether or not they lease hunting rights.

Being omnivorous, feral hogs can become predatory when the opportunity arises. Calves, kids, lambs, fawns, ground-nesting birds, reptiles and amphibians have been consumed by feral hogs. Hogs generally prey only upon young livestock, especially kids and lambs, but will take adult animals when the rare opportunity presents itself. When livestock depredation occurs, hogs are usually the last to receive blame because most people do not think of a hog as a predator. Hogs also carry off or thoroughly consume young prey leaving little, if any, evidence of the cause or source of livestock losses. Feral hogs are probably more scavenger than predator, so when evidence of livestock appears in the scat, it is difficult to determine whether a hog killed the livestock or simply fed on a carcass. There have been documented accounts of hog depredation on quail and turkey nests, but overall hog impact on quail nesting success is relatively minor. Some results indicate a higher incidence of nest damage in bottomlands due to the feral hogs’ preference for this habitat.

Disease and Parasites

Feral hogs may carry or transmit many diseases to humans and livestock such as pseudorabies, swine brucellosis, tuberculosis, tick-fever, rabies, anthrax and tularemia. The two diseases of feral hogs that are of most concern are pseudorabies and swine brucellosis.

Pseudorabies is a viral disease of the central nervous system that can affect domestic and feral hogs, and fatally affect cattle, horses, goats, sheep, dogs and cats. Wild animals such as raccoon, skunk, opossum and small rodents can also be fatally infected. Symptoms of the virus in these animals are anorexia, excessive salivation, spasms, convulsions and intense itching followed by paralysis and then death. Pseudorabies is not related to the rabies virus and does not infect people. This disease is of special concern to domestic hog owners because it can weaken pigs and cause abortions and stillbirths, thus decreasing production and profits. Once infected, the hog is a lifetime carrier and will periodically shed the virus through the mouth and nose. Transmission of the disease can be through direct contact, contaminated feed and water, ingestion of infected tissues or contaminated trailers.

Swine brucellosis can cause infertility in feral boars and abortions in feral sows. This disease can also cause a loss of production and profit in domestic swine operations. Swine brucellosis is transmitted to other hogs through reproductive discharges such as semen and afterbirth, and, once infected, a hog is a carrier for life. The only effective way to control this disease is to test and remove infected individuals, which is impossible in a wild population. Swine brucellosis is contagious to humans, through tissues, blood, urine and feces, and symptoms may range from severe flu-like symptoms to arthritis or meningitis. There is no cure for this disease in animals, but humans can be treated with antibiotics.

Main reservoirs of tuberculosis infection are in humans and cattle; however, feral hogs have been found infected with Mycobacterium bovis, the same strain of tuberculosis found in humans and cattle. Although the M. bovis strain has been detected in feral hogs, they are not very susceptible. The infection is most often contracted by ingestion of infected materials. Lesions on the lymph nodes are good indicators of an infected hog. Fortunately, due to extensive control measures, this disease is not common. Feral hogs may also carry another strain of tuberculosis, M. avis, contracted by eating dead birds. This strain is not contagious to humans.

Anthrax is a serious soil-borne disease most commonly associated with neutral or alkaline soils that serve as reservoirs for the organism’s spores. Recognized endemic areas include portions of Texas, Louisiana, California, Arkansas, Mississippi, Nebraska, South Dakota and small areas in other states. Even within these areas, anthrax occurs irregularly and primarily when the minimal daily temperature is above 60 degrees F. Although uncommon, the feral hog may become infected when feeding. Humans can contract this disease from contaminated animals or soil. The disease in humans is often fatal if not promptly treated with antibiotics.

Tularemia is not commonly found in feral hogs, but they can contract it through direct contact or ingestion of contaminated animal carcasses. Ticks can also transmit tularemia and are the most common source of infection for man. Persons who dress, prepare or eat improperly cooked feral hog or other wild game are also at increased risk.

Feral hogs harbor several parasites, some of which might pose problems for humans or other animals. Fleas, hog lice and ticks are common external parasites that a hog may acquire. Internal parasites can occur in feral hogs and may include roundworms, kidneyworms, lungworms, stomachworms, whipworms, liver flukes and trichinosis. Trichinosis infections in humans can be caused by consumption of undercooked infected pork.

Ranchers, farmers and hunters need to be aware of these potential diseases and take precautions to avoid infection. Livestock owners should ensure that their animals are vaccinated, especially when there is a chance they may have contact with feral hogs. There are state and federal laws governing the transport and relocation of feral hogs. Hunters, trappers, butchers and wildlife managers should always wear rubber gloves or other suitable hand protection when handling or dressing feral hogs. They should avoid contact with reproductive organs and blood, and wash thoroughly after contact. Hunters and chefs preparing feral hog meat should make sure it is thoroughly cooked.

Many people experiencing problems with hogs are eager to completely eliminate them. Their feelings are understandable, but extermination is very difficult. Feral hogs are prolific reproducers, adaptable and tenacious when it comes to survival. The most effective time to control feral hogs is when they first appear in an area. Once feral hogs are abundant, landowners may have to accept that they are permanent residents. Although total and permanent eradication is unlikely, there are several measures that can be used with some success to control numbers or prevent hog access. The most common measures include trapping, hunting and fencing.

Trapping

Trapping is probably the most commonly used technique and can be relatively effective for controlling feral hog numbers. Cage and corral-type traps are the most commonly used designs. These traps are not only effective at capturing feral hogs, but they usually are the best option to remove large numbers of hogs in a short period of time. Feral hogs are probably most susceptible to being trapped during winter or early spring because less food is available, making baiting more effective.

There are several cage or corral trap designs that can be used with the primary differences between most designs being door configuration, portability, flooring, roofing and size. A corral trap should be built large enough to hold several hogs, with bigger usually being better. This trap can be constructed out of steel panels with 4 inch by 4 inch or smaller mesh and t-posts.

Panels placed over the top are optional, but, without a top, some hogs may escape by climbing over the panels – especially if the trap is not checked regularly. An effective option to avoid completely enclosing the top is to cut panels into 1- or 1.5-foot widths and attach them along the edges of the top, extending to the inside, around the entire perimeter of the trap. This creates a “prison style” fence to help prevent feral hogs from climbing out.

There are several door designs that can be used with this trap, but the slide door (drop gate), spring door and lift door are most common. A trip wire should be used to trigger all three types of trap doors. The primary consideration for any door configuration is to frame the door so that, once inside, feral hogs can’t open the door with their snout.

If large enough, the corral trap design can catch sounders of 20 or more feral hogs at a time. The use of a Judas or decoy hog in a pen within the trap can also be very effective. However, this requires regular tending to keep the Judas hog fed and watered.

The portable cage trap equipped with a slide door or spring gate is also an effective design, but probably is more efficient when hog numbers are low. This trap’s best feature is that it is highly mobile, but has the disadvantages of trapping only a few hogs at a time and not being large enough to allow the use of a Judas hog. Portable cage traps can be designed many different ways including the style shown in Figure 4. Some are designed and sized to be loaded into the back of a pickup or trailer and hauled to the trap site. Others have been designed with an axle underneath where the tires can be lowered and raised using a boat winch. This allows the trapper to simply lower the tires, hook up to a vehicle and transport the trap to a desired site and then retrieve it with feral hogs inside to take them to a location where they can be dispatched.

For traps to be most effective, they should be placed in areas frequently used by feral hogs. Feral hogs are highly mobile, so finding the best locations may be difficult. A trap should be prebaited for a minimum of two or three days so feral hogs become accustomed to entering the trap. When prebaiting, trap doors should be fastened open to allow free access in and out of the trap. Initially, bait is usually placed outside the trap near the entrance in small piles or short lines to acclimate hogs to the trap’s presence. When hogs consume bait outside the trap, more bait can be placed at the entrance and just inside the trap. Prebaiting is complete when bait can be placed at the rear of the trap and hogs are freely entering and exiting the trap. At this time, the trap can be set. It is usually not necessary to go through the prebait process again unless the trap is moved to another location.

Bait used can range from homemade concoctions to specialized commercial blends, carrion or feedstuffs including whole corn, livestock cubes or soured grain. Whole corn is the easiest and the most commonly used bait. Traps should be checked daily, and captured hogs should be dispatched. Dispatching hogs in the trap may make subsequent trapping efforts in the same location more difficult. A better option, when the same location will be used again, would be to load captured hogs into a trailer and haul them to another area to be dispatched.

Traps and bait are available commercially. An online search for “wild or feral hog traps” or “wild or feral hog bait” will yield several sources.

Trap Configurations Photos

Hunting

Much feral hog hunting in Oklahoma is free with permission. However, leases specific to hog hunting, deer hunting leases that include hog hunting, and commercial or guided hog hunts are available.

The feral hog is not classified as a game animal in Oklahoma. However, a hunting license is required to hunt them on public hunting areas. Additionally, when hunting feral hogs on private or public land during any deer, elk or antelope season, hunters must possess a filled or unfilled license appropriate for the current season, area or zone unless exempt. Landowners may obtain a feral hog hunting permit from their local game warden for use during deer, elk or antelope season. Some hunting techniques result in the live capture of feral hogs and subsequent transportation of those hogs to other locations.

Under the 2007 Oklahoma House Bill 1914, no one can release a feral hog onto any unlicensed premise. Feral hogs can be released onto a licensed sporting or breeding facility, onto a licensed buying or gathering station, or onto a slaughter facility. It can be a felony to do otherwise, and penalties can be up to two years in prison and a fine of up to $2,000. Laws governing the transportation of feral hogs from other states into Oklahoma require a Certificate of Veterinary Inspection containing a written entry permit from the state of origin, individual identification of each animal and negative brucellosis and pseudorabies test results. Testing must be done within 15 days of importation, and animals testing positive for either disease must be immediately sent to slaughter or slaughtered on the premises.

Domestic hogs are occasionally raised as free-ranging animals, particularly in southeastern Oklahoma. Generally, free-ranging swine in other parts of the state are feral and not considered livestock. However, where feral hogs are hunted, an effort should be made to be sure the population is feral and landowner permission has been granted before hunting.

Hunting is probably second to trapping in terms of efficiency for reducing feral hog numbers. When combined, hunting and trapping can prove to be a very effective method of control. Hunting can be effective throughout the year and, in many areas, is becoming a popular sport as well. Some landowners are offering guided trophy hog hunts, turning a liability into an asset. Landowners who do not wish to lease their land can still use hunting as a tool for control and may choose to barter with hunters for other services.

There are many ways to hunt feral hogs including stand hunting from tree stands or blinds, still hunting and hunting with dogs. Stand hunting and still hunting are probably the two most popular methods, but hunting with dogs is becoming increasingly popular. Feral hogs taken while stand hunting are most commonly incidental to deer hunting. Stand hunting can be done over baited areas or in areas with abundant hog signs such as rooting, wallows or trails. Still hunting also can be done in similar areas and may be more successful due to the hogs’ mobility. Too often, hunters make the mistake of hunting areas that hogs are no longer using. Hog hunting can be a formidable sport with gun, bow, primitive firearm or handgun.

Feral hog hunting with dogs has become an established sport in Oklahoma. Trained dogs have proven to be efficient at capturing feral hogs. Like trapping, hunting hogs with trained dogs has been a proven way to remove feral hogs from suburban areas, golf courses and other populated areas where discharging a firearm may be illegal. Hunters using dogs generally ride horses or mules in order to keep up with the dogs. Most hunters have dogs that track and eventually bay the feral hog and dogs that catch the hog. Often, the catch dogs are leashed by the hunters until the other dogs bay the hog. Then the catch dogs are released to capture and hold the hog until the hunters arrive.

Aside from the obvious removal of hogs, there is another advantage to a landowner using hunting. When hunting efforts are intense, feral hogs often shift their home range, causing them to leave the property. A potential disadvantage of intense hunting pressure is hogs may change their activity periods, becoming more nocturnal. Nighttime shooting or hunting with dogs can be effective, but appropriate permits must be obtained from the local game warden. Due to the possible shifts in activity periods or home range, intense hunting pressure should be evaluated when trophy fees are collected for feral hog hunting.

Fencing

Using fences to control feral hogs is probably the most expensive option. Fencing large acreages seldom provides permanent control because feral hogs eventually find their way through most types of fences. Terrain is a major consideration when considering fencing. Canyons, creeks, ditches, etc., can create problem areas in a fence that hogs are sure to find. Chain link fence buried a foot underground, mesh wire fences, mesh wire fences combined with an electric wire and multiple strand electric fences have proven effective. Electric fence is not 100 percent effective, but research has shown multistrand electric fences with wire spaced 8 and 18 inches above the ground reduce intrusions by about half. Because of cost and maintenance requirements, electric fences used alone or in combination with other fence types are most practical for small areas.

Toxicants

Toxicants are not legal for feral hogs in the U.S. because there are none registered for use on feral hogs. Studies have shown the use of toxicants is considerably less expensive than other control methods in terms of cost per feral hog removed, but research and development costs have been a deterrent to developing a registered toxicant for the U.S. Other problems with using a toxicant are non-target species impacts through consumption of bait or the ingestion of infected meat and the lower priority of feral hog control relative to other species.

Predators

Another ally in the control of feral hogs is the coyote. Piglets and small hogs are frequently eaten by coyotes, and coyote populations have been known to increase as feral hog populations increase. However, the extent that coyotes control hog populations remains to be verified. Owls and bobcats also have been documented as predators of piglets and small pigs. Mountain lion and black bear also are known predators.

Feral hogs represent many unknowns, and, as one biologist so precisely put it, “feral hogs are an ecological black box.” In some areas, feral hogs have been blamed for declining quail populations, yet there are other areas where both quail and feral hog numbers are high. Feral hogs have also been accused of having a significant negative impact on wild turkey nests, various plant species and entire ecological systems. The actual effect feral hogs have on our environment, however, is largely unknown. More research and practical knowledge is needed to provide a better understanding of the feral hog and its influence on game and nongame species and the environment.

We know feral hogs can harbor and transmit some diseases and parasites to livestock and humans, and they can have a significant negative impact on some livestock operations through depredation and damage to forages, facilities and fences. Farmers are perhaps the most affected because of the damage caused by rooting and depredation of crops. Feral hogs provide excellent table fare and are a challenging game species to pursue with gun, bow or dog; they even compete with white-tailed deer in some areas as the most popular animal to hunt. To effectively get the upper hand on this prolific species, intensive implementation of control practices by landowners and others is necessary. Many pros and cons regarding the status of these creatures remain and probably will as long as we have biologists, farmers, ranchers, hunters and, of course, the feral hog.

Organizations

- Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry

- Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation: Game Division

- Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service

Online Resources

- Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation: Feral Hog Questions and Answers

- Texas Parks and Wildlife: Feral Hogs

- Texas AgriLife Extension Service

References

United States Department of Agriculture. (1992). Wild Pigs: Hidden Danger for Farmers and Hunters. Bulletin Number 620.

Barrett, R. H. and G. H. Birmingham. 1994. Wild Pigs. pp. D-65 – D70 in S. E. Hygnstrom, R. E. Timm and G. E. Larson, editors.

Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage. Great Plains Agriculture Council, Wildlife Committee, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Davidson, W. R. (editor). 2006. Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases in the Southeastern United States, (3rd edition). Southeastern Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study. University of Georgia, Athens.

Hanselka, C.W. and J.F. Cadenhead, Editors. (1993). Feral Swine: A Compendium for Resource Managers. Texas Agriculture Extension Service, San Angelo.

Mayer, J.J. and I.L. Brisbin, Jr. (1991). Wild Pigs in the United States: Their History, Comparative Morphology, and Current Status. The University of Georgia Press, Athens.

Mendoza, M., Jr. and S.H. Turman. (1991). Controlling Feral Hog Damage. Texas Animal Damage Control Service. Leaflet Number 1925, San Antonio.

Rollins, D. (1994). Feral Hogs in Texas: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. Texas Agriculture Extension Service, San Angelo. (video).

Taylor, R. (1991). The Feral Hog in Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Federal Aid Report Series Number 28, Austin.

Article Reprint

For article reprint information, please visit our Media Page.